Personal aggression and behavioral deviations in seniour pupils in context of physical education lessons

ˑ:

PhD. Biol. M.A. Shanskov1

Dr.Hab., Professor G.N. Ponomarev2

1 National Research University ‘Higher School of Economics – Saint Petersburg’

2 Russian State Teachers Training University named after A.I. Gertsen, Saint Petersburg

Keywords: personal aggression, behavioural deviations, pupils, physical education.

Introduction

Aggressive behaviour implies different attacking actions intended to demonstrate personal superiority in force or apply force to other person(s) or inanimate thing(s) that the actor of aggression strives to damage. Modern manifestations of aggressive behaviour in most cases are caused by neurotic personal protesting against different stress factors including stressful social environment conditions that the actor of aggression fails to adapt to; and this is the reason for considering aggressive behaviour as an opposition to an adaptive behavioural model.

It was for the last few years that the analysts have been concerned by the increasingly aggressive behaviour of schoolchildren. Increased aggression, as reasonably stated by V.V. Glebov and G.G. Arkelov, may be viewed as a form of response to the growing physical and mental discomforts, stresses and frustration. It may serve as an instrument for the actor to attain some personally meaningful goal(s), including, among other things, self-assertion and social status improvement benefits [2]. Moreover, it is quite natural in any child’s development process that some degree of aggression is generated and demonstrated. Low degrees of demonstrative aggressiveness are normally associated with passive individual behavioural models dominated by conformism, whilst high degrees of personal aggressiveness may be indicative of a social behavioural model dominated by competitive attitudes and interpersonal confrontations that trigger conflicts with surrounding people; such behaviour may be quite destructive for personal success in any activity.

A few studies have provided accounts of prudently structured physical education lessons being of positive impact on the current aggressiveness levels as an important tool that helps correct (i.e. reasonably decrease or increase) these levels [1, 2]. These studies provided fairly convincing data and analysis that give the reasons to believe that physical education lessons help optimize mental conditions of pupils, improve their social statuses and scale down their anxiety. It should be noted, however, that no data may be found on the gender-specific variations of the pupils’ aggressiveness scores in the context of physical education lessons, and no comparative analyses have been made to benchmark the available adolescent pupils’ aggression scores against that of the adult athletes. Therefore, we initiated this study in an attempt to bridge this gap.

Objective of the study was to explore gender-specific variations of the pupils’ aggressiveness scores in the context of physical education lessons and benchmark them against the relevant scores of adult athletes.

Methodology and structure of the study

We used the following methods for the purposes of the study: Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (BDHI) test in application to personal aggression scoring; the risk-taking scale of the Eysenck Personality Inventory in the version adapted by K.V. Sugonyaev; and the A.N. Orel psychometric inventory of “disposition to behavioural deviations” [3, 4]. We used standard blank forms for the survey and the outcome scores were processed using MultiPsychometer programmed psycho-diagnostic complex. Description of the test procedure may be found in the Instruction Manual to the MultiPsychometer complex [4]. The psychometric test results were normalized using Sten [Standard Ten] scores. Subject to the study were 134 young people including 95 pupils aged 15-17 years from 10-11 grades of Public School #15 of Saint Petersburg; 39 ice hockey players from “SCA” Ice Hockey Club (Saint Petersburg); and the National Women’s Ice Hockey Team players. The psychometric test results were processed using standard methods of variation statistics and correlation analysis.

Study results and discussion

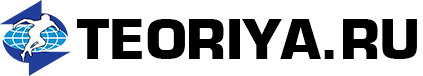

Given in Table 1 and Figures 1 and 2 hereunder are the scores of verbal (VA), physical (PA), mental (MA), emotional (EA), auto-aggression (AA) and general (GA) aggression. Verbal aggression is normally manifested by one’s resentment being verbalized to other person, with the aggressor striving to offend the latter. It is the adolescent male athletes that are tested with the highest VA scores, the scores being meaningfully higher than that for the young male non-athletes (p˂0.001) and young female athletes (p˂0.05). Test results for the male and female adolescent non-athletes (beyond the regular school sport curriculum) show no meaningful differences. Physical aggression (PA) is manifested by physical assault of one person on another with brutal physical force being used. It is again the adolescent male athletes who are tested with the highest PA scores that are significantly higher than that for their peers-non-athletes (p˂0.05) and adolescent female athletes (p˂0.001). The young female non-athletes are tested with notably lower PA scores than that for the National Women’s Ice Hockey Team players (p˂0.05) and adolescent male non-athletes (p˂0.001). The “SCA” Ice Hockey Club (St. Petersburg) adult male athletes showed the PA scores notably higher than that of the adult female athletes of the same sport discipline (p˂0.001). As far as the mental aggression (MA) scores are concerned (mental aggression being normally manifested by aggressive attacks on inanimate surrounding things), the subject groups showed generally the same scores in this test category, with no significant differences revealed.

Table 1. Verbal (VA), physical (PA), mental (MA), emotional (EA), auto- (AA) and general (GA) aggression scores obtained by the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (BDHI) test of the subject groups

|

Test group |

VA |

PA |

MA |

EA |

AA |

GA |

|

Adolescent female non-athletes (n=38) |

5,00±0,34 |

3,58±0,33 |

5,29±0,39 |

5,92±0,37 |

6,97±0,31 |

5,92±0,30 |

|

Adolescent male non-athletes (n=33) |

4,45±0,30 |

5,03±0,37 |

4,61±0,45 |

5,82±0,40 |

5,82±0,46 |

5,73±0,35 |

|

Adolescent female athletes (n=8) |

4,88±0,85 |

3,88±0,48 |

4,50±0,57 |

4,38±0,78 |

6,38±0,82 |

5,13±0,58 |

|

Adolescent male athletes (n=16) |

6,31±0,41 |

6,44±0,45 |

5,44±0,57 |

6,31±0,47 |

6,19±0,61 |

6,94±0,47 |

|

National Women’s Ice Hockey Team players (n=26) |

4,58±0,35 |

4,54±0,38 |

4,27±0,38 |

4,50±0,48 |

4,73±0,44 |

4,08±0,40 |

|

“SCA” Ice Hockey Club (St. Petersburg) players (n=13) |

4,46±0,56 |

6,08±0,40 |

4,15±0,50 |

3,54±0,49 |

4,23±0,39 |

4,85±0,41 |

Figure 1. Verbal (VA), physical (PA) and mental (MA) aggression scores for the tested pupils and athletes (n=134)

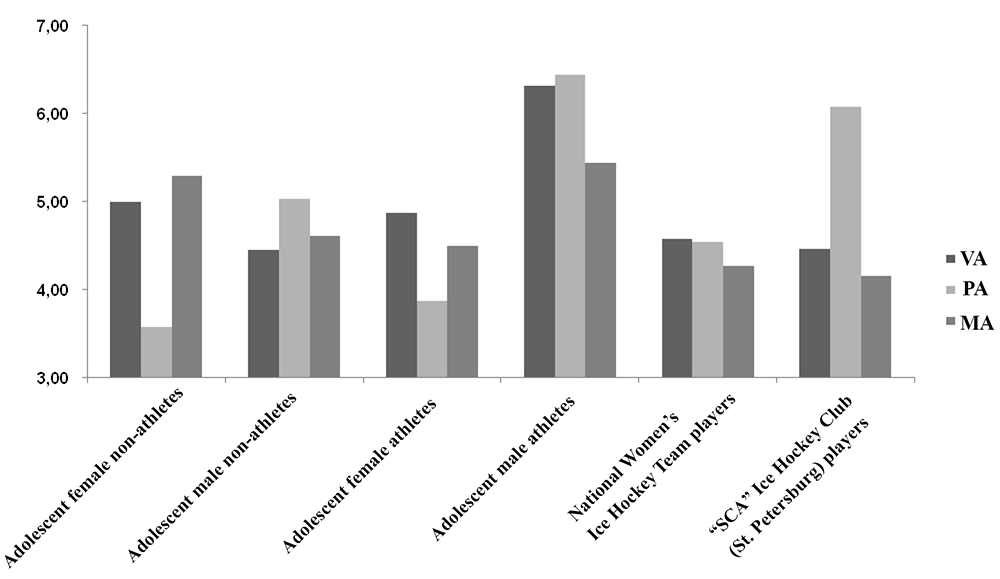

Emotional aggression (EA) is normally manifested in emotional resentment in contacts with some other person(s), with a variety of feelings dominated by suspicion, hostility, aversion and malevolence to this person. The tests showed that leading in the EA scores are the adolescent male athletes and school-aged non-athletes. Adult male athletes and adolescent female athletes were tested with relatively low EA scores. Furthermore, the tests revealed meaningful differences of the EA scores between the adolescent female non-athletes and the peer female athletes (p˂0.05) including the National Women’s Ice Hockey Team players (p˂0.05). The EA scores of the “SCA” Ice Hockey Club (Saint Petersburg) adult male athletes were significantly lower than that of the adolescent male athletes (p˂0.001) and adolescent male non-athletes (p˂0.01). The adolescent male athletes showed much higher EA scores than the adolescent female athletes (p˂0.05).

Auto-aggression (AA) is typically triggered by a state of unhappiness when the actor fails to be in peace with oneself and surrounding world when his/her “identity” protection mechanisms are weakened or non-existent and, as a result, the person feels unsafe in the aggressive environment. Tested with the highest AA scores were both of the adolescent women groups and the adolescent male athletes group, whilst the adult male athletes showed the lowest AA scores. The adolescent female non-athletes' AA scores were found meaningfully different from that of the National Women’s Ice Hockey Team players (p˂0.001) and the adolescent male non-athletes (p˂0.5); whilst the “SCA” Ice Hockey Club (St. Petersburg) adult male athletes were significantly different (p˂0.05) in their AA scores from the adolescent male athletes and adolescent male non-athletes groups (p˂0.05).

As for the general aggression (GA) scores, all the adolescent groups were tested with the highest GA scores versus that for the adult athletes; with the adolescent male athletes group showing a significant difference from the peer adolescent male non-athletes group (p˂0.05), the adolescent female athletes group (p˂0.05) and the “SCA” Ice Hockey Club (Saint Petersburg) adult male (p˂0.01); and the same applies to the GA scores of the adolescent female non-athletes versus the National Women’s Ice Hockey Team players (p˂0.001).

Figure 2. Emotional (EA), auto- (AA) and general (GA) aggression scores for the tested pupils and athletes (n=134)

Therefore, the psychometric tests showed clear age-specific stratification of the aggression scores. Total aggression scores of the adolescent people, regardless of the degrees of their involvement in sport, were found much higher than that of the adult athletes. The psychometric test results were also found to be gender-specific. Adolescent female non-athletes, for instance, showed lower PA scores and notably high AA scores versus that of the adolescent male non-athletes. Young women engaged in sports showed lower aggression scores – in contrast to the adolescent men who were tested with higher aggression scores when engaged in sports compared to the scores of their peers-non-athletes. However, we should not rule out that the adolescents doing sports may be more prone to biological natural aggressiveness that may be one of the factors motivating them for sport. This factor deserves being studied in detail.

Having analysed the scores generated by the two other psychometric questionnaires, we would make an emphasis, first of all, on the scores of “disposition to behavioural deviations”. It is a matter of common knowledge that asocial delinquent behaviour (DB) is typical for the individuals falling in conflict with the generally accepted living standards and legal framework. On the “disposition to behavioural deviations” scale, the adolescent male athletes group was scored by 6.31±0.64 stens, the score being meaningfully higher (p˂0.05) than that for the adolescent male non-athletes with their 4.88±0.88 stens. It should be noted that the second key factor of these psychometric tests – that is the “addictive behaviour” (AB) typically meaning the ones’ disposition to abstract away from reality through deviational action on the mental condition – was found to show much the same picture. The adolescent male athletes were also found to score high on this scale, with their score of 6.06±0.66 stens being meaningfully higher (p˂0.05) than 4.70±0.43 stens scored by the adolescent male non-athletes. This scale was found gender-unspecific as the tested men and women showed no meaningful difference in the scores. As far as the correlations of these scores with the aggression scores are concerned, we would note that reliable correlation ratios were found for the DB vs. GA scores (0.50) and the DB vs. PA scores (0.45) of the tested groups. The correlation ratio of the AB vs. PA scores was found to make up 0.38; and that for the AB vs. GA scores was estimated at 0.36. There are good reasons to believe, therefore, that sport exercises may be recommended to the adolescent men of this group since selective sports may give the means to release their natural age-specific high aggressiveness in the most safe manner and, at the same time, prevent the young people from entering the risk zone of addictive behaviour.

The survey data obtained for the risk-taking scale under the relevant personality psychometric questionnaire was found to show much the same picture. The adolescent male athletes showed the highest “risk-taking” (RT) and “disposition to collision” (DC) scores versus that of the other tested groups, with their RT scores of 6.06±0.49 stens and DC scores of 6.31±0.44 stens. The RT scores of the peer adolescent male (p˂0.05) and female non-athletes (p˂0.01) were found significantly different. Individuals tested with the high RT scores may be described as “gamers” who appreciate risks for the special flavour and bitterness they bring to life, as they tend to believe. In terms of the DC scores this group was also found different from the same groups of adolescent male and female non-athletes (p˂0.001).

Conclusion

The study demonstrated the personal aggression scores being clearly gender-dependent as verified by the tests of the adolescent men and women groups. As far as the adult athletes are concerned, men showed higher scores only in the physical aggression aspect, whilst the aggressiveness scoring profiles of the adolescents of both sexes were much more complicated. The adolescent male athletes were found to have higher verbal, physical and general aggression scores than their peer non-athletes, whilst the adolescent female athletes were less prone to aggression of any type. Therefore, sport exercises were found to be of different effects on personality aggression patterns, and this knowledge may be beneficial for corrective actions in the education process focused on the behavioural deviations diagnosed in pupils.

References

- Borisenkova E.S. Vliyanie zanyatiy fizicheskoy kul'turoy na samootsenku lichnosti shkol'nikov 11 – 13 let (Effect of exercises on self-esteem of pupils aged 11 - 13 years) / E.S. Borisenkova, A.Ya. Nayn // Teoreticheskie i prikladnye aspekty sovremennoy nauki. 2014. # 5-6. - P. 36-39.

- Glebov V.V. Organizatsiya dosugovoy deyatel'nosti shkol'nikov kak sredstvo profilaktiki agressivnogo sotsial'nogo povedeniya v detsko-podrostkovoy srede (Organisation of leisure activities of pupils to prevent aggressive social behaviour among children and adolescents) / V.V. Glebov, G.G. Arakelov // Vestnik Moskovskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta kul'tury i iskusstv. 2012. # 6 (50). - P. 146-151.

- Kleyberg Yu.A. Sotsial'naya psikhologiya deviantnogo povedeniya (Social psychology of deviant behaviour). – Moscow: Sfera, 2004, - P. 141-154.

- Sugonyaev K.V. Apparatno-programmny psikhodiagnosticheskiy kompleks Multipsikhometr: Metodicheskoe rukovodstvo (MultiPsychometer programmed psycho-diagnostic complex: Methodical manual) / K.V. Sugonyaev, A.Yu. Chuplin, E.V. Medvedev et al. // JSC "Scientific-Production Center DIP" . – Moscow. 2008. Part 1: – 366 p.

Corresponding author: g-ponomarev@inbox.ru